Page links:

Homo sapiens

Out of Africa

3 types of DNA

My DNA tests

My Autosomal DNA

My Viking DNA

Doggerland

Doggerland videos

My Y-DNA

Notable Y-DNA connections

Ancient Y-DNA connections

Tollense battlefield 1300 BCE

My Neanderthaler DNA

Migration analysis

My mtDNA

Notable mtDNA connections

Ancient mtDNA connections

My mtDNA origins

My ticket to Mars

This is my personal “Out of Africa story”, my ancestral migration 200.000 thousand years ago from North East Africa to Western Europe and finally sending my name to Mars on the NASA Perseverance Rover, 18-02-2021.

—————————–

“Our own genomes carry the story of evolution, written in DNA, the language of molecular genetics and the narrative is unmistakable.

– Kenneth R. Miller –

Homo sapiens

The species that you and all other living human beings on this planet belong to is Homo sapiens. During a time of dramatic climate change 300,000 years ago, Homo sapiens evolved in Africa. Like other early humans that were living at this time, they gathered and hunted food, and evolved behaviors that helped them respond to the challenges of survival in unstable environments.

Humans (Homo sapiens) are the most abundant and widespread species of primates, characterized by bipedality and large complex brains enabling the development of advanced tools, culture and language. Humans evolved from other hominins in Africa several million years ago.

In his book The history of the human brain, Bret Stetka writes: “By human, I don’t just mean Homo Sapiens, the species we belong to, but any other member of the genus Homo. We have gotten used to being the only human species on Earth, but in our not-so-distant past – probably a few hundred thousand years ago – there were at least nine of us running around. There was Homo habilis, or “the handy man” and Homo erectus, the first “pitcher”.

The Denisovans roamed Asia, while the more well-known Neanderthalers spread through Europe. But with the exception of Homo sapiens, they are all gone.”

Homo sapiens emerged around 300,000 years ago, evolving from Homo erectus and migrating out of Africa, gradually replacing local populations of archaic humans.

Early humans were hunter-gatherers, before settling in the Fertile Crescent and other parts of the Old World. Access to food surpluses led to the formation of permanent human settlements and the domestication of animals.

Out of Africa

In paleoanthropology, the recent African origin of modern humans, also called the “Out of Africa” theory (OOA), recent single-origin hypothesis (RSOH), replacement hypothesis, or recent African origin model (RAO), is the dominant model of the geographic origin and early migration of anatomically modern humans (Homo sapiens). It follows the early expansions of hominins out of Africa, accomplished by Homo erectus and then Homo neanderthalensis.

The model proposes a “single origin” of Homo sapiens in the taxonomic sense, precluding parallel evolution of traits considered anatomically modern in other regions, but not precluding multiple admixture between H. sapiens and archaic humans in Europe and Asia. H. sapiens most likely developed in the Horn of Africa between 300,000 and 200,000 years ago. The “recent African origin” model proposes that all modern non-African populations are substantially descended from populations of H. sapiens that left Africa after that time.

There were at least several “out-of-Africa” dispersals of modern humans, possibly beginning as early as 270,000 years ago, including 215,000 years ago to at least Greece,and certainly via northern Africa and the Arabian Peninsula about 130,000 to 115,000 years ago. These early waves appear to have mostly died out or retreated by 80,000 years ago.

The most significant “recent” wave out of Africa took place about 70,000–50,000 years ago, via the so-called “Southern Route”, spreading rapidly along the coast of Asia and reaching Australia by around 65,000–50,000 years ago, while Europe was populated by an early offshoot which settled the Near East and Europe less than 55,000 years ago.

In the 2010s, studies in population genetics uncovered evidence of interbreeding that occurred between H. sapiens and archaic humans in Eurasia, Oceania and Africa indicating that modern population groups, while mostly derived from early H. sapiens, are to a lesser extent also descended from regional variants of archaic humans.

There are three types of DNA

- Y-DNA

Because Y-chromosomes are passed from father to son virtually unchanged, males can trace their patrilineal (male-line) ancestry by testing their Y-chromosome.

Because Y-chromosomes are passed from father to son virtually unchanged, males can trace their patrilineal (male-line) ancestry by testing their Y-chromosome.

Since women don’t have Y-chromosomes, they can’t take Y-DNA tests (though their brother, father, paternal uncle, or paternal grandfather could). Y-chromosome testing uncovers a male’s Y-chromosome haplogroup, the ancient group of people from whom one’s patrilineage descends. Because only one’s male-line direct ancestors are traced by Y-DNA testing, no females (nor their male ancestors) from whom a male descends are encapsulated in the result.

- Autosomal DNA

Autosomal DNA tests trace a person’s autosomal chromosomes, which contain the segments of DNA the person shares with everyone to whom they’re related (maternally and paternally, both directly and indirectly.

Autosomal DNA tests trace a person’s autosomal chromosomes, which contain the segments of DNA the person shares with everyone to whom they’re related (maternally and paternally, both directly and indirectly.

The autosomal chromosomes gives you information that is most useful in looking back a couple of centuries.

Because everyone has autosomal chromosomes, people of all genders can take autosomal DNA tests, and the test is equally effective for people of any gender. With an autosomal test, your results won’t include information about haplogroups

- mtDNA

Mitochondrial DNA tests trace people’s matrilineal (mother-line) ancestry through their mitochondria, which are passed from mothers to their children.

Mitochondrial DNA tests trace people’s matrilineal (mother-line) ancestry through their mitochondria, which are passed from mothers to their children.

Mitochondrial DNA testing uncovers a one’s mtDNA haplogroup, the ancient group of people from whom one’s matrilineage descends.

Because mitochondria are passed on only by women, no men (nor their ancestors) from whom one descends are encapsulated in the results.

Since everyone has mitochondria, people of all genders can take mtDNA tests.

What and where did I test and an explanation of some important used DNA concepts

I chose FamilyTreeDNA from Houston, Texas, USA, because they are considered the best option for dedicated mtDNA and Y-DNA testing. They’re the only company to offer dedicated mtDNA and Y-DNA testing. Established in 2000, they have a longer history of offering the service than most, and are highly regarded among the genealogy community. FamilyTreeDNA takes your privacy very seriously and will never share your test results with any other company. In fact, one of the reasons they are so popular is because they have a great track record of keeping your information safe, and of never sharing it

But remember, they are not cheap if you decide to go for the full package, as I did, but I think well worth the money.

Their Y-DNA testing has four levels based on how many markers you want to analyze: 37, 67, 111, and the BIG-Y with 700. You can easily upgrade without taking a new test. I started with the 37 marker test, but upgraded to the BIG-Y 700 text. FamilyTreeDNA has 2 different mtDNA tests; plus and full sequence. I decided to take the full sequence test.

So these are my tests:

* Family Ancestry – Autosomal DNA

* Paternal Ancestry – Y-DNA and

* Extended Paternal Ancestry – BIG Y-DNA

* Maternal Ancestry – full sequence mtDNA

Explore here which tests are best for you and learn more about your ancestry:

The result for the customer who takes the Big Y test is that the haplogroup predicted through STR testing is confirmed and generally several more branches and leaves are added to your own personal haplogroup tree.

Family Tree DNA very accurately predicts your branch haplogroup when you take an STR test, but it’s a major branch, near the tree, not a small branch and certainly not a leaf. Smaller branches can’t be accurately predicted nor larger branches confirmed without SNP testing. The most effective way to SNP test for already discovered haplogroups – plus new ones never before found – perhaps unique to your line – is to take the Big Y.

The Big Y:

- Confirms estimated haplogroups.

- Provides you with your haplogroup closest in time – meaning puts twigs and leaves on your branches.

- Helps to build the Y DNA tree, meaning you can contribute to science while learning about your own ancestors.

- Confirms that men who do match on the same STR markers really ARE in the same haplogroup.

- Shows matches further back in time than STRs can show.

- Maps the migration of the person’s Y line ancestors.

Attachment of HIV to a CD4+ T-helper cell: 1) the gp120 viral protein attaches to CD4. 2) gp120 variable loop attaches to a coreceptor, either CCR5 or CXCR4. 3) HIV enters the cell.

My CCR5 test results

- My FamilyTreeDNA CCR5 test showed that my delta 32 value was NORMAL, so there was no 32 base deletion.

CCR5 is a gene on chromosome 3, the CCR5 test is for a 32 base deletion (delta 32) that has been speculatively linked to survival during the Black Death and the Small Pox Plagues that decimated the population of Europe during the Middle Ages.

The mutation in CCR5 known as Delta 32 causes a change in the protein that makes it non-functional. Carrying two copies of the mutation protects most carriers from HIV. The delta 32 mutation is found in between 5% and 14% of Europeans and is rare in Asians and Africans. Because the CCR5-delta32 variant is found in such a clear geographical pattern, researchers believe that its prevalence has been shaped by the survival advantage it provided at one time. This mutation has not been found in people from African, East Asians descent thus far.

When confronted with a deadly disease, for example, a particular gene variant might give a survival advantage to those in the population that happen to have it. If most of those who do not have the variant die, a higher proportion of individuals in the next generation will have the gene variant.

- But since the CCR5-delta32 variant doesn’t adversely affect one’s health, why are researchers studying it?

Because the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) uses the CCR5 protein to infect immune cells. To put in in simple terms, it is a portal of entry for HIV virus to enter into the immune cells of the human body. Think of CCR5 as a door. The HIV virus uses it to enter into immune cells in the human body. Because of the mutation, it causes the “door” to be “locked” thus preventing HIV virus from entering the immune cell.

Generally, if you have a double mutation of the gene for CCR5, you have high resistance to HIV infection but it may not be absolute as there have been cases of persons with both mutated genes and yet became HIV infection.

The Black Death

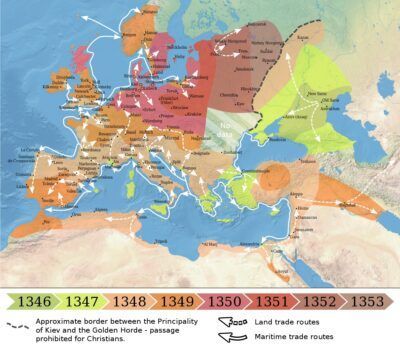

Spread of the Black Death in Europe and the Near East (1346–1353)

Map made by O.J. Benedictow

Recent research has suggested plague first infected humans in Europe and Asia in the Late Neolithic-Early Bronze Age.Research in 2018 found evidence of Yersinia pestis in an ancient Swedish tomb, which may have been associated with the “Neolithic decline” around 3000 BCE, in which European populations fell significantly. This Y. pestis may have been different from more modern types, with bubonic plague transmissible by fleas first known from Bronze Age remains near Samara.

The Black Death (also known as the Pestilence, the Great Mortality or the Plague) was a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Afro-Eurasia from 1346 to 1353. It is the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, causing the death of 75–200 million people in Eurasia and North Africa, peaking in Europe from 1347 to 1351. Bubonic plague is caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis, but it may also cause septicaemic or pneumonic plagues.

The Black Death was the beginning of the second plague pandemic. The plague created religious, social and economic upheavals, with profound effects on the course of European history.

The origin of the Black Death is disputed. The pandemic originated either in Central Asia or East Asia but its first definitive appearance was in Crimea in 1347.[6] From Crimea, it was most likely carried by fleas living on the black rats that travelled on Genoese slave ships, spreading through the Mediterranean Basin and reaching Africa, Western Asia and the rest of Europe via Constantinople, Sicily and the Italian Peninsula. There is evidence that once it came ashore, the Black Death was in large part spread by fleas – which cause pneumonic plague – and the person-to-person contact via aerosols which pneumonic plague enables, thus explaining the very fast inland spread of the epidemic, which was faster than would be expected if the primary vector was rat fleas causing bubonic plague.

The Black Death was the second great natural disaster to strike Europe during the Late Middle Ages (the first one being the Great Famine of 1315–1317) and is estimated to have killed 30 percent to 60 percent of the European population. The plague might have reduced the world population from c. 475 million to 350–375 million in the 14th century. There were further outbreaks throughout the Late Middle Ages and, with other contributing factors (the Crisis of the Late Middle Ages), the European population did not regain its level in 1300 until 1500. Outbreaks of the plague recurred around the world until the early 19th century.

This map shows the approximate location of the ice-free corridor and specific Paleoindian sites. Credit: Roblespepe, CC BY-SA 3.0 Wikipidea Commons

FamilyTree DNA also offers the D9S919 test, it is a test that gives you an indication if you have Native American ancestry. Of course in my case that is highly improbable, but just out of curiosity I decided to test it also.

D9S919 is a STR marker located on chromosome 9. It was previously known as D9S1120 and under this name it was reported that an allele value of 9 was only found in the Americas and far eastern Asia.

Three independent lines of genetic evidence support the claim (Shields et al. 1993) of an ancient gene pool that included the ancestors of the modern inhabitants of Western Beringia and the Americas. The presence of an allele value of 9 is therefore a strong indication of native American ancestry somewhere within a person’s pedigree.

- My allele value with the D9S919 test came out as 16-17, so what does that mean?

Well D9S919 is present in only around 30% of the Native Americans. So about 70% do not have it. However, since only about 30% of Native Americans have that count, the fact that you don’t have 9 for that marker means it’s inconclusive from that result whether you have Native American ancestry. You either don’t have Native American ancestry or you are part of the 70% of people with Native American ancestry who don’t have 9 for D9S919.

- Or as in my case, because I am 100 % European, I have no Native American ancestry

Y-DNA haplotype

A Y-DNA haplotype is a persons Y-STR profile. This includes the number of repeats at specific Y-STR markers. Y-DNA haplotypes are useful for tracing recent paternal lineages and connections. Haplotype is actually short for “haploid genotype” and refers to the combination of genetic markers in multiple locations in a single chromosome. If two people match exactly on all of the markers they have had tested, they share the same haplotype and are related.

World Map of Y-Chromosome Haplogroups – Dominant Haplogroups in Pre-Colonial Populations with Possible Migrations Route. Credit: Chakazul, Wikimedia Commons

What are Haplogroups

Y-DNA haplogroups are determined by testing Y-SNPs. Your Y-DNA haplogroup represents “deep ancestry” or ancient family group. A haplogroup is a series of mutations present in a chromosome. It is therefore detectable in an individual’s DNA and may vary from one population to another, or even from one person to another.

Every person belongs to a certain haplotype and therefore to a certain haplogroup, so it can be traced back to where a person’s origin lies on the basis of genography.

There is a male and a female haplogroup classification. The Y chromosome (Y DNA) is used to distinguish the male haplogroups (Y chromosome haplogroup) and the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) to distinguish the female haplogroups (mitochondrial haplogroup). The X chromosome is not usable because the X chromosome is not recombining, but it is difficult to trace over several generations.

SNP’s

SNP’s (pronounced “snips”) is an abbreviation of single nucleotide polymorphisms, they are the most common type of genetic variation among people. Each SNP represents a difference in a single DNA building block, called a nucleotide. SNP’s occur normally throughout a person’s DNA. They occur almost once in every 1,000 nucleotides on average, which means there are roughly 4 to 5 million SNPs in a person’s genome. These variations may be unique or occur in many individuals; scientists have found more than 100 million SNP’s in populations around the world.

Once a SNP mutation occurs, it will typically be passed through subsequent generations and is unlikely to revert back to the default value. As such, SNP testing can be used to understand a genetic family tree (called a haplotree.) SNP tests, such as the BIG Y-700 test from FamilyTreeDNA (my yDNA test), provide details on haplotree branching, as well as much better estimates of time to most recent common ancestor (TMRCA) than STR tests do.

- SNPs are mutations that occur along the Y – Chromosome

- SNPs are the basis for Branches on the Haplotree

- Each Male Line has its own Unique set of SNPs

- SNPs occur on Average of once every 144 years

- Until a SNP is “named”, it is referred to as an “Unnamed Variant”

- After a BIG Y-700 is completed, Unnamed Variants are your most recent SNP

- Mutations – and will form new Branches below your “Terminal” SNP once theyare named

BIG Y – 700 is identifying more SNPs/Variants than previous BIG-Y Tests. All of these SNPs/Variants are not among your most recent mutations, but may be inserted anywhere along the Haplotree. Some SNPs/Variants may come from portions of the Y – Chromosome that are not used for Dating, and some (few) may be bad reads.

TMRCA

TMRCA (the most recent common ancestor) is the amount of time or number of generations since individuals have shared a common ancestor. Since mutations occur at random, the estimate of the TMRCA is not an exact number (i.e., seven generations) but rather a probability distribution. As more information is compared, the TMRCA estimate becomes more refined.

Terminal SNP

Y-DNA haplogroups are defined by the presence of a series of SNP markers on the Y chromosome. Subclades a term used to describe a subgroup of a subgenus or haplogroup) defined by a terminal SNP, the SNP furthest down in the Y chromosome phylogenetic tree.

Your “Terminal” SNP does not always represent your MRCA

- The term “Terminal” SNP is used to represent the most current SNP placed on your portion of the Haplotree.

- If you have Unnamed Variants, or a Block of Equivalents associated with your Bottom Step, your portion of the Haplotree is incomplete, and it does not represent your actual “Terminal SNP”.

- The Convergence Date of your Bottom Step is NOT always the Time to Most Recent Common Ancestor.

The Gregorian calendar is the global standard for the measurement of dates. Despite originating in the Western Christian tradition, its use has spread throughout the world and now transcends religious, cultural and linguistic boundaries.

As most people are aware, the Gregorian calendar is based on the supposed birth date of Jesus Christ. Subsequent years count up from this event and are accompanied by either AD or CE, while preceding years count down from it and are accompanied by either BC or BCE.

- BC and AD

The idea to count years from the birth of Jesus Christ was first proposed in the year 525 by Dionysius Exiguus, a Christian monk. Standardized under the Julian and Gregorian calendars, the system spread throughout Europe and the Christian world during the centuries that followed. AD stands for Anno Domini, Latin for “in the year of the Lord”, while BC stands for “before Christ”. - BCE and CE

CE stands for “common (or current) era”, while BCE stands for “before the common (or current) era”. These abbreviations have a shorter history than BC and AD, although they still date from at least the early 1700s. They have been in frequent use by Jewish academics for more than 100 years, but became more widespread in the later part of the 20th century, replacing BC/AD in a number of fields, notably science and academia. - YBP and BP

This is a year designation alternative to the widely-used but Christian-oriented BC and AD and their secular equivalents BCE and CE. Before Present (BP) years, or “years before present” is a time scale used mainly in archaeology, geology, and other scientific disciplines to specify when events occurred before the origin of practical radiocarbon dating in the 1950s. Because the “present” time changes, standard practice is to use 1 January 1950 as the commencement date (epoch) of the age scale.

Current Status and Recommendations

Most style guides do not express a preference for one system, although BC/AD still prevails in most journalistic contexts. Conversely, academic and scientific texts tend to use BCE/CE. Since there are compelling arguments for each system and both are in regular use, we do not recommend one over the other. Given the choice, writers are free to apply their own preference or that of their audience, although they should use their chosen system consistently, meaning BC and CE should not be used together, or vice versa. There are also some typographical conventions to consider:

- BC should appear after the numerical year, while AD should appear before it.

1100 BC, AD 1066 - BCE and CE should both appear after the numerical year.

1100 BCE, 1066 CE - As is the case with most initialisms, periods may be used after each letter.

1100 B.C., A.D. 1066, 1100 B.C.E., 1066 C.E. - Some style guides recommend writing BC, AD, BCE and CE in small caps.

AD 2017 - YBP and BP should both appear after the numerical year.

Formed 1400 YBP, TMRCA 325 YBP

Of course, writers often don’t need to make the choice at all. The BCE/CE (or BC/AD) distinction is usually unnecessary outside of historical contexts, and it is generally understood that when unspecified, the year in question is CE (or AD). As a result, dates that occurred within the last few centuries are rarely marked with CE (or AD).

My Autosomal DNA

If you look at the map, my Autosomal results indicate that my very early ancestors lived in geographic lands later occupied by Angles, Saxons, Jutes, Frisians, Danes, Vikings, Scandinavians and Normans. If you read on you will see that my Y-DNA and mtDNA haplogroups probably reconfirm these findings.

My paternal cousins (people you can trace to with only this male line) were probably among the first (re)settlers of Britain, Ireland, and Scandinavia as the ice sheets receded.

The result of my Autosomal DNA analysis shows that my origins are 100% Western Europe.

Scandinavia 21%

From about 44,000 years ago, humans intermittently lived in the northwestern region of Europe between periods of glaciation due to the Ice Age. Around 13,000 BCE, they returned to the northwestern region of Europe including the British Isles via a land bridge connecting them.

Towards the end of the 4th millennium BCE, Hunter-Gatherers cultivated crops, domesticated animals, and made tools such as hand axes and pottery. The construction of large stone monuments, such as those found at Stonehenge, began by 3000 BCE.

Doggerland during the Anglian glaciation

Land bridge between the mainland and Britain – Doggerland and Dogger Bank. Comparison of the geographical situation in 2000 to the late years of the Vistula-Würm Glaciation. Map made by: Francis Lima“

Until the middle Pleistocene Great Britain was a peninsula of Europe, connected by the massive chalk Weald–Artois Anticline across the Straits of Dover. During the Anglian glaciation, about 450,000 years ago, an ice sheet filled much of the North Sea, with a large proglacial lake in the southern part fed by the Rhine, the Scheldt and the Thames.

Doggerland was an area of land, now submerged beneath the southern North Sea, that connected Great Britain to continental Europe. It was flooded by rising sea levels around 6500–6200 BCE. Geological surveys have suggested that it stretched from what is now the east coast of Great Britain to what are now the Netherlands, the western coast of Germany and the peninsula of Jutland. It was probably a rich habitat with human habitation in the Mesolithic period.

Around 7000 BC the Ice Age had ended and Mesolithic European hunter-gatherers had migrated from their refuges to recolonize the continent, including Doggerland which later submerged beneath the rising North Sea.

When scientists from Imperial College released a simulation of a tsunami, triggered by a vast undersea landslide at Storrega off the coast of Norway around 6000 BC, it probably came as a surprise to many in north-west Europe that their reassuringly safe part of the world had been subject to such a cataclysmic event.

The researchers suggest that this succession of destructive waves up to 14 metres high may have depopulated an area that is now in the middle of the North Sea, known as Doggerland. However, melting ice at the end of the last ice age around 18,000 years ago led to rising sea levels that inundated vast areas of continental shelves around the world. These landscapes, which had been home to populations of hunter gatherers for thousands of years were gradually overwhelmed by millions of tonnes of meltwater swelling the ocean. Doggerland, essentially an entire prehistoric European country, disappeared beneath the North Sea, its physical remains preserved beneath the marine silts but lost to memory.

The majority of western European males belonged to Y-haplogroup I and northeast Europeans to haplogroup R1a. Other minor male lineages such as R1b, G, J, T and E would also have been present in Europe, having migrated from the Asian Steppe, the Middle East and North Africa.

Anglosaxon migration.

Credit: Jones and Mattingly’s map

Anglo-Saxons

The Anglo-Saxon period in Britain spans approximately the six centuries from 410-1066 AD. The period used to be known as the Dark Ages, mainly because written sources for the early years of Saxon invasion are scarce. However, most historians now prefer the terms ‘early middle ages’ or ‘early medieval period’.

It is speculated that Celtic languages arrived in Britain with the influx of the Bell Beaker culture from Central Europe, which was defined by bell-shaped vessels.Anglo-Saxons is the collective name for the various Germanic tribes that settled in England after the departure of the Romans in 407, in the course of the 5th century and later.

The later invading tribes came from northwestern Germany and the Netherlands (the Angles and the Saxons and also the Frisians) and from Denmark (the Jutes).

Climate change had an influence on the movement of the Anglo-Saxon invaders to Britain: in the centuries after 400 AD Europe’s average temperature was 1°C warmer than we have today, and in Britain grapes could be grown as far north as Tyneside. Warmer summers meant better crops and a rise in population in the countries of northern Europe.

At the same time melting polar ice caused more flooding in low areas, particularly in what is now Denmark, Holland and Belgium. These people eventually began looking for lands to settle in that were not so likely to flood. After the departure of the Roman legions, Britain was a defenceless and inviting prospect.

The Saxons settled in the south of the country, the Jutes in the southeast (Kent), the Angles occupied the largest area: the center and north. Around 840 the invasions of the Danes (also called Vikings or Normans) started and at the time of King Alfred the Great they controlled a large part of the country.

The attacks of the Normans ceased and the populations intermingled. At the end of the 10th century, the Danes resumed their attacks. Later Norman influence increased, culminating in the Norman conquest of England by William the Conqueror in 1066.Low Countries and Vikings

Before the Netherlands was the Netherlands or even Holland, it was known as Frisia. According to historians, Vikings came to Friesland in the 9th century. They established control over all of Friesland.

During the last years of Charlemagne’s reign (768-814) the emperor took measures against the danger of Viking raids. He stationed fleets in the major rivers and organized coastal defenses. After 820, the defense system in the northern part of the Carolingian state collapsed. Between 834 and 837 the city of Dorestad (near present-day Wijk bij Duurstede, about 70 km from where I live, Dordrecht) was destroyed four times. Without much opposition, Walcheren in Zeeland (where the Kloosterman Family originated) was taken in 837.

Already before 840 the Danish Vikings Harald and Rorik became vassals of Lothar (grandson of Charlemagne) and received Walcheren and Dorestad as fiefs. This tactical move did not bring peace.Until 873 there are regular reports of Viking attacks and in 863 Dorestad was again destroyed. This time the city was not rebuilt, also because the river became sandy. Bishop Hunger of Utrecht fled in 858 to Roermond and later to Deventer. In 873, the Normans in Oostergoo,

Friesland (Friesland) were defeated by an army led by an immigrant Viking. In Flanders, the Vikings regularly sailed up the Scheldt from 851 to 864 and attacked the cities of Ghent and the districts of Mempiscus and Terwaan. countries from Denmark) turned their attention to England.

The impact of the raids on everyday life must have been great, but perhaps not as great as ecclesiastical sources suggest. Churches and monasteries were almost always visited, for the simple reason that they had valuable property. Of course, the clergy described the Vikings as fierce pagans who turned the coastal areas into ruins. Politically, the Vikings stimulated the further disintegration of the Carolingian Empire. Because they encountered little resistance, they preferred robbers to traders. As vassals they played a role in the conflicts between Lotharius and Charles the Bald (ca. 840) and later (ca. 870) between Charles the Bold and Louis the German.

Areas subjected to settlement and raids by Vikings and Normans (Max Naylor, public domain Wikipedia Commons)

After the victory of Alfred the Great of Wessex (878) the Vikings returned to the lowlands. This time they also fought as land soldiers and were equipped with horses. Flanders was particularly hard hit (Ghent, Terwaan, Atrecht, Kamerijk). Louis III defeated the Vikings in 881 at Saucourt on the River Somme. This battle was described in Ludwig’s Lied (Ludwigslied). According to the Fulda Annals, Louis’ army killed 9,000 Danes. As a result, the Vikings returned to Flanders and Dutch Limburg. From Asselt (north of Roermond) they attacked cities in Germany (Cologne, Bonn) and Limburg (Liège, Tongeren). In their attack on Trier they were opposed by the bishops Wala and Bertulf of Trier and by Count Adelhard of Metz. Following the example of Trier, other cities began to defend themselves effectively.

The new emperor Charles the Fat sent an army to Asselt. The two Viking leaders, Godfried and Siegfried, were forced to negotiate. Godfrey chose to stay. He became a vassal of the emperor and, after being baptized, married Gisela, daughter of Lothair II, the first king of Lorraine. Siegfried was paid off with 2,000 pounds of silver and gold and set out for the north with 200 ships. Emperor Charles felt threatened by Godfried and his (Godfried’s) brother-in-law Hugo (Gisela’s brother).

In June 885 Godfried was invited for talks in Spijk, near Lobith. This turned out to be a conspiracy and Godfrey was murdered. Hugo was blinded and transferred to the monastery of Prüm for the rest of his life. Here the monk Regino wrote the story of his downfall. In September 891 the Vikings lost a battle at the river Dyle, near Leuven against King Arnulf of Carinthia. The Fulda Annals tell us that the bodies of dead Vikings blocked the flow of the river. The poor harvest of 892 and the threat of famine caused the Vikings to move north again. After 892 their role in the low countries was limited to occasional raids (particularly in Nijmegen, Groningen, Stavoren, Tiel and Utrecht). After 1010 the raids came to an end.

The Viking era lasted from 789 CE to approximately 1066 CE and had an enduring impact upon the peoples of Europe.

The image of the Vikings that most of us have grown up with – the image in popular culture – is that of a tall, bearded, blond man on a longboat. Probably wearing a style of horned helmet, he’s a battle-hardened warrior heading out on a raiding mission to kill in and to steal from coastal towns or monasteries in the rest of Europe.

In truth, the stories of these terrifying Norsemen (men from the North) are mostly told by their survivors, as in their early years there was no written record kept by Scandinavian people themselves . This means that – until recently – we had to rely on the writings of people from outside of Scandinavia, people who might have had a vested interest in portraying Vikings in a negative light, and later on writings from towards the end of the Viking age after the introduction of Christianity into Scandinavia. These were written by people who – again – might have had an interest in showing the civilising effects of their new, more modern, ways.

While all Vikings were Norsemen, not all Norsemen were Vikings. These raiders were in fact only a subgroup of the Norse population; they all desired the opportunities and wealth that foreign lands could offer, whether through conquest or through trade and settlements for better farming and fishing.

I uploaded my DNA sample to LivingDNA. The test generates two pieces of information.

- My “Viking Index” (a score between 0 and 100%) and it represents the amount of DNA that I share with ancient Vikings and a “Viking Population Match” which identifies which of four Viking populations I most closely match.

- The four choices are Norwegian Vikings, Swedish and Danish Vikings, British and North Atlantic Vikings, and Eastern European Vikings.

According to LivingDNA my Viking index is 38% and I am most closely associated with the Vikings of Denmark and Sweden.

According to LivingDNA my Viking index is 38%. That means that I am most closely associated with the Vikings of Denmark and Sweden.

Viking Index

The Viking index represents the amount of DNA that I share with ancient Vikings. First, the genetic similarities between my DNA and the DNA obtained from ancient viking and non-viking samples are computed.

LivingDNA allows us to estimate how much DNA I share with each group. In order to then interpret and contextualise this calculation, they compare my value to that of all other Living DNA users. This yields my Viking Index score.

The Viking Index score allows you to see where your result falls in comparison to the whole range of Viking Indexes across the Living DNA user base. For example, if your Viking Index is 80%, this means that your DNA is more similar to Viking DNA than 80% of all Living DNA customers.

The Viking Population Match

The Viking Population match indicates which Viking population my DNA is most similar to. LivingDNA has identified 4 distinct Viking populations from their analysis of ancient DNA. These are Norwegian Vikings, Swedish and Danish Vikings, British and North Atlantic Vikings, and Eastern European Vikings. They compare my DNA data to genetic models describing the genetic similarity and variability of these populations in order to identify my closest match.

Ancient Viking DNA

A total of 446 Viking samples were used for the LivingDNA analysis. Ancient human remains from the Viking Age were excavated in a diverse set of 80 archaeological sites within the current borders of the United Kingdom (including mainland Great Britain and the Orkney Islands), Ireland, Iceland, Denmark (mainland, the Faroe Islands and Greenland), Norway, Sweden, Estonia, Ukraine, Poland and Russia.

Samples were excavated in the major areas of Viking influence and have been dated to between the late 8th and late 11th centuries CE. Human remains were excavated from burial sites. Most regions that were once inhabited by Vikings saw a gradual increase in the use of inhumation burials (opposite to cremation burials) during the Viking Age as a result of the adoption of Christian burial practices in Scandinavia and the Baltic Sea area from the 10th century onwards.

This implies that there is a limited bioarcheological record of human remains from the Early Viking Age, whereas it is much richer for the latter stages of the Viking Age. It must be taken into account that the record of individuals given an archaeologically visible burial is highly skewed towards social elites, who maintained wider networks and enjoyed higher degrees of mobility than the average person – this is relevant when assessing population mobility and diversity.

Ancient human remains (mostly teeth or petrous bones) were processed and DNA was extracted and sequenced in order to be used to generate our Viking Index and Viking Population Match results. The Viking genetic data was retrieved from three scientific publications Margaryan et al., 2020, Krzewińska et al., 2018, Ebenesersdóttir et al., 2018.

Dupuytren’s contracture (also called Dupuytren’s disease, Morbus Dupuytren, Viking hand and Celtic hand) is a condition in which one or more fingers become permanently bent in a flexed position. The disease comes from Scandinavia, possibly brought here by the Vikings. It’s mainly of genetic origin and therefore often runs in families.

The condition caused the growth of new tissue in the hands and fingers. Since these tissues have a habit of contracting, the condition often results in flexion deformities of the fingers.Dupuytren’s disease is currently called a Viking disease on the assumption that the disease was spread to Europe and the British Isles during the Viking Age of the 9th to the 13th centuries. From a literature search, it is proposed that Dupuytren’s disease existed in Europe earlier than the Viking Age and originated much earlier in prehistory.

There is a strong genetic component, certain HLA haplotypes also appear to be associated with the disease. It is strongly associated with northern European ancestry, and could have arisen from a genetic mutation in the Viking population originally.

Researchers have also discovered a link between Neanderthal genetic material and Dupuytren’s disease (Viking’s disease). Neanderthals living 40,000 to 50,000 years ago undoubtedly suffered from some form of this condition. Through genetic mixing they passed this vulnerability on to humans living alongside them in Northern Europe.

Viking’s Disease’ Traced Back to Ancestral Neanderthals

Living reconstruction in the Neanderthal Museum (Erkrath, Mettmann) of a Homo sapiens neanderthalensis.

Researchers have discovered a link between Neanderthal genetic material and an unusual health disorder that affects modern humans. The disorder in question is Dupuytren’s disease, a.k.a. Viking’s disease, a hand condition that can cause some of a person’s fingers to become permanently bent at an angle.

Neanderthals living 40,000 to 50,000 years ago undoubtedly suffered from some form of this condition. Through genetic mixing they passed this vulnerability on to humans living alongside them in Northern Europe.

As explained in a new paper just published in Molecular Biology and Evolution , Dupuytren’s disease is far more common in people of Northern European descent than in those whose predecessors came from Africa. In fact, the name “Viking disease” comes from its predominance among descendants of the ancient Viking warriors who once ruled Scandinavia.

Highlighting the latter relationship, one study found that about 30 percent of Norwegians above the age of 60 experience the symptoms of Dupuytren’s disease, usually in their middle and/or ring fingers. “This is a case where the meeting with Neanderthals has affected who suffers from illness,” said the paper’s lead author, evolutionary geneticist Hugo Zeberg from the Karolinska Institute in Solna, Sweden. Nonetheless, he emphasized that it is important not to overstate the connection between Vikings and Neanderthals.

Viking’s Disease: Then and Now

It was in Europe that much of the interbreeding between Neanderthals and modern humans occurred between 42,000 and 65,000 years ago. African populations lived separately from Neanderthals, who occupied Eurasia exclusively. As a result, people of African descent only possess traces of Neanderthal DNA today.

In 1999, a Danish study of twins determined that the development of Dupuytren’s disease is most heavily influenced by heredity, with its heritability factor estimated to be at 80 percent. While other risk factors for the condition have been identified, including age, alcohol use and diabetes, a genetic predisposition must always be present.

This means that Neanderthal genetic material absorbed into the human genome is, in a very real sense, the true cause of this condition. It was the prevalence of Dupuytren’s disease among Northern Europeans in particular that intrigued the scientists enough to motivate their study of the condition’s genetic origins.

To facilitate their research, the team of experts led by Hugo Zeberg analyzed data collected from 7,871 people with the disorder and 645,880 control subjects listed in the UK Biobank , the FinnGen R7 collection and the Michigan Genomics Initiative. Their purpose was to identify the presence of genetic variants that could be connected to Dupuytren’s disease.

Through extensive comparative analysis, scientists identified 61 genetic variants associated with Viking’s disease, with three of them known to originate from Neanderthals. Most significantly, the second and third most strongly associated variants came from the Neanderthals, suggesting that these extinct human cousins were particularly susceptible to Dupuytren’s disease.

The scientists taking part in the study believe that the widespread prevalence of this condition in present-day human populations would be highly unlikely without there having been contact and interbreeding with Neanderthal populations.

Neanderthal DNA: A Curse, a Blessing, or a Mixture of Both?

Studies have shown that about two percent of the human genome is comprised of DNA sourced from distant Neanderthal ancestors. Only trace amounts are found in those who are descended from people who lived in sub-Saharan Africa, based on the lack of Neanderthal penetration into that part of the world.

While it might not sound like all that much, human development has been significantly impacted by the presence of this genetic material. The study linking so-called Viking’s disease to Neanderthal genes is not particularly surprising, because other studies have found a clear connection between our Neanderthal generic inheritance and various human health conditions.

For example, comprehensive research published in 2014 found links between Neanderthal genes and type 2 diabetes , Crohn’s disease, biliary cirrhosis (an autoimmune disease of the liver) and incidence of depression. Recent studies have even suggested a link between Neanderthal genes and susceptibility to Covid-19 .

These genes didn’t necessarily introduce new types of ill health to the human gene pool. But they did increase the likelihood of certain disorders developing. Further research may indicate that other human health conditions are affected by Neanderthal DNA in the same way.

For the most part, Neanderthal genes are concentrated in areas that code for the creation of human skin and hair. Scientists believe this DNA was picked up and passed on because it had survival advantages: Neanderthal contributions would have given humans the ability to grow thicker hair and skin, which would have helped protect them from the colder climates they encountered in Eurasia once they’d left the African continent.

Given the assumptions behind this theory, the persistence of Neanderthal genes that increase disease risk seems surprising, since this DNA would reduce survival chances rather than increasing them. It’s possible that Neanderthal genes have survived in humans as a result of random chance, offering benefits in some cases and increasing vulnerability in others.

What all the research shows conclusively is that Neanderthal genes do have a significant impact on human health and development. In the context of Viking’s disease, Neanderthals introduced a genetic condition to the human gene pool that is unpleasant but does not pose a significant threat to survival. The majority of individuals affected by this disorder were likely unaware of their Neanderthal genetic heritage until now. However, with this recent scientific revelation, it is probable that they will never forget their newfound ancestral Neanderthal connection.

- Source and credit:

Article by By Nathan Falde, published in Ancient Origins. - Top image: My hand with Viking’s disease, a.k.a. Dupuytren’s contracture, a condition of the hand that can cause some of a person’s fingers to become permanently bent at an angle. Photo made by Cees Kloosterman

- Neanderthal hunters depicted in the Gallo-Romeins Museum Tongeren (Belgium), Trougnouf (Benoit Brummer), CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Well I have Dupuytren’s contracture and my father and grandfather, so this genetic mutation certainly runs in my family.

So were some of my early ancestors Viking?

Genetic ancestors shared by two individuals are detectable by regions of matching DNA. With every generation there is a chance that each region will be split by the shuffling, so they inevitably get shorter over time. By finding the length of the longest region shared by the two individuals, one can estimate the time passed since the most recent shared genetic ancestor.

The ubiquity of the term “Viking” masks a wide variety of constructions of Vikingism: the old northmen are merchant adventurers, mercenary soldiers, pioneering colonists, pitiless raiders, self-sufficient farmers, cutting-edge naval technologists, primitive democrats, psychopathic berserks, ardent lovers and complicated poets.

- Wow … that sounds just like me, so do I have some Viking in my DNA?

Well, considering that 56 % of my Autosomal DNA origins are from England, Wales and Scotland, 23 % from Scandinavia and that my main Y-DNA I-FGC151505 haplogroup is most commonly found in England and Denmark and that my LivingDNA Viking Index is 38% makes it an interesting idea and certainly not a far-fetched possibility.

Viking identity was not limited to people with Scandinavian genetic ancestry. The genetic history of Scandinavia was influenced by foreign genes from Asia and Southern Europe before the Viking Age. Many Vikings have high levels of non-Scandinavian ancestry, both within and outside Scandinavia, which suggest ongoing gene flow across Europe.”

- Maybe the answer to my Vikings ancestry should be, “Yes, we all are Vikings… and Romans, Huns and Slavs and we are also all Africans and Asians.

Historical and geographic information about my Autosomal DNA

From about 44,000 years ago, humans intermittently lived in the northwestern region of Europe between periods of glaciation due to the Ice Age. Around 13,000 BCE, they returned to the northwestern region of Europe including the British Isles via a land bridge connecting them.

Towards the end of the 4th millennium BCE, Hunter-Gatherers cultivated crops, domesticated animals, and made tools such as hand axes and pottery. The construction of large stone monuments, such as those found at Stonehenge, began by 3000 BCE. It is speculated that Celtic languages arrived in Britain with the influx of the Bell Beaker culture from Central Europe, which was defined by bell-shaped vessels.

Within the last 2,000 years, Britain has been subject to many migrations. In the 1st century CE, the Romans invaded and established settlements across what is now modern-day England and Wales. The Romans were besieged by attacks from local tribes, such as the Scots, Picts, and Iceni.

Other invading groups such as the Anglo-Saxons, who arrived on the east coast of Britain around the time of the fall of the Roman Empire, were also met with resistance from the many local tribes. However, over the next 200 years, Anglo-Saxon warrior lords divided the region into large Germanic kingdoms, assimilating or displacing Briton and Pictish inhabitants, and eradicated Roman culture.

By the 7th century CE, Christian monasteries were established, and a unified English language was formed. In the 8th and 9th centuries, Vikings from Scandinavia raided parts of the British coast and established colonies throughout modern-day Scotland and England.

In 843 CE, Kenneth MacAlpin united the Picts and Scots to form the nation of Alba, which is the Gaelic name for Scotland, although many Scottish islands remained under Scandinavian control until the 1400s. Welsh leaders in the 9th century united the kingdoms of Gwynedd, Morgannwg, and Powys and fought off Irish occupation of the region, although further attempts to unite the region were unsuccessful.

The first English kingdom was formed at the end of the 9th century when Alfred the Great defeated the Vikings in modern-day England. Within 200 years, the newly established English kingdom was lost to the invading French-Normans led by William the Conqueror. William’s soldiers were rewarded with land, titles, and power, and French-Norman rule and culture were imposed across England and Wales.

Since the French-Norman Conquest, the English peoples fought for several centuries to regain their lost rights. Despite numerous rebellions against French-Norman rulers and their descendants, all of Wales fell under the control of the English monarchy by the 13th century CE and remains part of Great Britain today. Scottish kings waged war with the French-Normans in England and continued to fight off English occupation for many years until Stewart King James VI of Scotland inherited the English throne and united the two nations in the 16th century CE. While the foundation for conquests in the Americas was laid with his predecessor Queen Elizabeth I, King James I established the first successful British colonies in the Americas during the 17th century CE. The British Empire continued their conquest and expanded their rule and culture around the globe, colonizing large regions of North and South America, Africa, Asia, and Oceania.

Around 40,000 years ago, much of Central Europe was occupied by Hunter-Gatherers of the Aurignacian culture who produced distinct stone blades, projectile points, and other tools made of bone. Beginning around 7,000 years ago, groups from the Middle East introduced farming and the practice of large-scale collective burials along with stonework architecture, such as the Carnac stones in Brittany, France.

In the late 4th millennium BCE, settlers from the Pontic steppe arrived in Central Europe. They brought a new social and economic order centered around horsemanship. This interaction influenced the formation of the Corded Ware culture throughout Europe, whose presence is marked by pottery with rope-like designs. The arrival of these Indo-European speakers from the Pontic steppe introduced language families like Germanic and Celtic to areas of modern-day Germany and France.

Beginning in 58 BCE, the Celtic and Germanic tribes of Gaul, which is now modern-day France, engaged in warfare with an invading Roman Empire. By 50 BCE, Rome was triumphant and integrated Gaul into their empire. As Roman power declined, the Germanic Goth and Vandal tribes from the unconquered Magna Germania, now modern-day Germany, invaded the lands Romans abandoned. When Roman power was effectively gone in the region, Gaul disbursed into many small states from which emerged the single powerful state of the Franks.

The Franks were a Germanic peoples who, as they spread across Gaul, integrated Gallo-Roman peoples into their young empire. The Franks embraced aspects of Gallo-Roman culture such as their Latin-based language and Christianity. The Holy Roman Emperor Charlemagne became a pivotal figure in the history of Western and Central Europe. His ever-growing empire which annexed territories throughout Europe led him to be named Holy Roman Emperor. As Holy Roman Emperor, he strove to revive the grandeur of the western Roman Empire in the 8th century. However, after the death of Charlemagne’s son Louis I a generation later, the Holy Roman Empire was divided into three kingdoms: the West Frankish, East Frankish, and Middle Kingdom. The East Frankish and Middle kingdoms eventually formed part of a reborn Holy Roman Empire centered in what is modern-day Germany.

By the 18th century CE, the Germanic states of Austria and Prussia emerged as dominant forces after the second Holy Roman Empire’s dissolution. By the 19th century, the Germanic states had formed a confederation that attempted economic and cultural integration, a precursor to the modern German state. In its western divisions, the fall of the Holy Roman Empire led to the formation of West Francia, the precursor to the kingdom of France.

Centralization of a French state was the main trend, but by the 1500s, a period of expansion began. In the 16th century, the kingdom of France conquered large portions of North and South America. Post-revolutionary France expanded further once again into Central Europe under Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte in the first part of the 19th century. After his defeat, France turned its attention to conquering regions of West Africa and Southeast Asia. While Germany, after national unification in the 1870s, embraced imperialism, and within a few short years, conquered enough territory in Africa to become the third-largest empire of the day. Today, France is a multi-ethnic nation with many of its residents having come from former colonies. In Germany, the national psyche and economy have rebuilt themselves since World War II and the Cold War. Today, Germany plays a key role in the European Union. The history of colonialism and the many divisions and unifications in Central Europe sparks the everlasting question of what it means to be French and German.

As the ice sheets retreated toward the end of the last Ice Age in Europe, Hunter-Gatherers entered the southern region of Scandinavia around 11,7000 years ago. Scandinavia was one of the last places to be re-settled in Europe. Hunter-Gatherer groups arriving from continental Europe formed a culture known for their pitted earthenware.

About 6,000 years ago, Neolithic Farmers from Southern Europe established settlements throughout Scandinavia. Neolithic Farmers co-existed with Hunter-Gatherers for many hundreds of years; however, Farming groups eventually dominated the region. From 3000 BCE, Central Europe’s Corded Ware culture spread to southern Scandinavia, bringing their Indo-European languages with them. The Indo-European language branched into many languages, such as Proto-Germanic, which spread throughout this area.

Roman historians make few references to the peoples of Scandinavia as the Roman Empire, at its height in 117 CE, reached just south of Scandinavia. However, archaeological sites show that the Scandinavian region was composed of organized state-like groups with extensive trade networks into Central Europe.

The earliest preserved proto-Norse writings in the form of runestones appear around the 4th century. The most notable expansion of Scandinavian peoples occurred between the 9th and 11th centuries CE, which took place during the Viking era when ancient Norse peoples came to settle or raid parts of northern Western Europe and Eastern Europe. Notably, islands in the North Atlantic, like Iceland, Greenland, and the Faroe Islands, were discovered by ancient Norse settlers. Icelandic explorer Leif Erikson also found and established a short-lived settlement in Newfoundland.

Various kingdoms have established unions with one another throughout Scandinavia. The three Scandinavian kingdoms of Norway, Denmark, and Sweden were joined in 1387 as a result of the Kalmar Union under Queen Margaret I of Denmark. After the secession of Sweden from the Kalmar Union in 1397, the Scandinavian countries waged multiple wars against each other throughout the centuries. Control over the various nations changed hands many times and Sweden rose and fell as a Northern European power. Sweden had ruled Finland since the Second Swedish Crusade in the 13th century, and in 1809, they were forced to surrender the area to Russia after the Finnish War. After the Napoleonic Wars, Denmark and Norway’s union split, and Norway and Sweden formed a union until 1905. After World War II, Scandinavian countries along with Finland developed the Nordic model, which aims to combine an emphasis on public welfare with free-market capitalism.

Percentages of autosomal DNA that I still carry with me

The climate during the Pleistocene Epoch (2.6 mill – 11,700 YA) fluctuated between episodes of glaciation (or ice ages) and episodes of warming, during which glaciers would retreat. It is within this epoch that modern humans migrated into the European continent at around 45,000 years ago.

These Anatomically Modern Humans (AMH) were organized into bands whose subsistence strategy relied on gathering local resources as well as hunting large herd animals as they travelled along their migration routes. Thus these ancient peoples are referred to as Hunter-Gatherers. The timing of the AMH migration into Europe happens to correspond with a warming trend on the European continent, a time when glaciers retreated and large herd animals expanded into newly available grasslands.

Evidence of hunter-gatherer habitation has been found throughout the European continent from Spain at the La Brana cave to Loschbour, Luxembourg and Motala, Sweden. The individuals found at the Loschbour and Motala sites have mitochondrial U5 or U2 haplogroups, which is typical of Hunter-Gatherers in Europe and Y-chromosome haplogroup I. These findings suggest that these maternally and paternally inherited haplogroups, respectively, were present in the population before farming populations gained dominance in the area.

Based on the DNA evidence gathered from these three sites, scientists are able to identify surviving genetic similarities between current day Northern European populations and the first AMH Hunter-Gatherers in Europe. The signal of genetic sharing between present-day populations and early Hunter-Gatherers, however, begins to become fainter as one moves further south in Europe. The hunter-gatherer subsistence strategy dominated the landscape of the European continent for thousands of years until populations that relied on farming and animal husbandry migrated into the area during the middle to late Neolithic Era around 8,000–7,000 years ago.

Roughly 8,000–7,000 years ago, after the last glaciation period (Ice Age), modern human farming populations began migrating into the European continent from the Near East. This migration marked the beginning of the Neolithic Era in Europe. The Neolithic Era, or New Stone Age, is aptly named as it followed the Paleolithic Era, or Old Stone Age.

Tool makers during the Neolithic Era had improved on the rudimentary “standard” of tools found during the Paleolithic Era and were now creating specialized stone tools that even show evidence of having been polished and reworked. The Neolithic Era is unique in that it is the first era in which modern humans practiced a more sedentary lifestyle as their subsistence strategies relied more on stationary farming and pastoralism, further allowing for the emergence of artisan practices such as pottery making.

Farming communities are believed to have migrated into the European continent via routes along Anatolia, thereby following the temperate weather patterns of the Mediterranean. These farming groups are known to have populated areas that span from modern day Hungary, Germany, and west into Spain.

Remains of the unique pottery styles and burial practices from these farming communities are found within these regions and can be attributed, in part, to artisans from the Funnel Beaker and Linear Pottery cultures. Ötzi (the Tyrolean Iceman), the well-preserved natural mummy that was found in the Alps on the Italian/Austrian border and who lived around 3,300 BCE, is even thought to have belonged to a farming culture similar to these. However, there was not enough evidence found with him to accurately suggest to which culture he may have belonged.

Although farming populations were dispersed across the European continent, they all show clear evidence of close genetic relatedness. Evidence suggests that these farming peoples did not yet carry a tolerance for lactose in high frequencies (as the Yamnaya peoples of the later Bronze Age did); however, they did carry a salivary amylase gene, which may have allowed them to break down starches more efficiently than their hunter-gatherer forebears.

Further DNA analysis has found that the Y-chromosome haplogroup G2a and mitochondrial haplogroup N1a were frequently found within the European continent during the early Neolithic Era.

Following the Neolithic Era (New Stone Age), the Bronze Age (3,000–1,000 BCE) is defined by a further iteration in tool making technology. Improving on the stone tools from the Paleolithic and Neolithic Eras, tool makers of the early Bronze Age relied heavily on the use of copper tools, incorporating other metals such as bronze and tin later in the era. The third major wave of migration into the European continent is comprised of peoples from this Bronze Age; specifically, Nomadic herding cultures from the Eurasian steppes found north of the Black Sea. These migrants were closely related to the people of the Black Sea region known as the Yamnaya.

This migration of Bronze Age nomads into the temperate regions further west changed culture and life on the European continent in a multitude of ways. Not only did the people of the Yamnaya culture bring their domesticated horses, wheeled vehicles, and metal tools; they are also credited for delivering changes to the social and genetic makeup of the region. By 2,800 BCE, evidence of new Bronze Age cultures, such as the Bell Beaker and Corded Ware, were emerging throughout much of Western and Central Europe. In the East around the Urals, a group referred to as the Sintashta emerged, expanding east of the Caspian Sea bringing with them chariots and trained horses around 4,000 years ago.

These new cultures formed through admixture between the local European farming cultures and the newly arrived Yamnaya peoples. Research into the influence the Yamnaya culture had on the European continent has also challenged previously held linguistic theories of the origins of Indo-European language. Previous paradigms argued that the Indo-European languages originated from populations from Anatolia; however, present research into the Yamnaya cultures has caused a paradigm shift and linguists now claim the Indo-European languages are rooted with the Yamnaya peoples.

By the Bronze Age, the Y-chromosome haplogroup R1b was quickly gaining dominance in Western Europe (as we see today) with high frequencies of individuals belonging to the M269 subclade. Ancient DNA evidence supports the hypothesis that the R1b was introduced into mainland Europe by the Bronze Age invaders coming from the Black Sea region. Further DNA evidence suggests that a lactose tolerance originated from the Yamnaya or another closely tied steppe group. Current day populations in Northern Europe typically show a higher frequency of relatedness to Yamnaya populations, as well as earlier populations of Western European Hunter-Gatherer societies.

My Y-DNA

Out of Africa migration to Western Europe of my Haplogroup I-FGC15105

FTDNA Globe trekker EUROPE view of the lineages through time and place and to uncover the modern history of my (I-FGC15105) direct paternal surname line and the ancient history of my shared ancestors. In addition to my own (I-FGC15105) ancestral line (thick red line), the thin red lines shows lineages that went other ways and the migration paths leading up to my Ancient Connections.

The Bab-el-Mandeb, meaning “Gate of Tears” in Arabic, is a strait between Yemen in the Arabian Peninsula, Djibouti, and Eritrea, north of Somalia, in the Horn of Africa, connecting the Red Sea to the Guardafui channel and the Gulf of Aden. It is also called Mandab Street in English language.

![]() 4 -6 million years BCE

4 -6 million years BCE

Humans split off from their common ancestor with the chimpanzees and gorillas between 4 million and 6 million years ago. All of humanity may be descended from a small tribe of about 10,000 people, some of whom migrated out of Africa within the past 200,000 years or so.

As of 2010, there are two main accepted dispersal routes for the out-of-Africa migration of early anatomically modern humans, the “Northern Route” (via Nile Valley and Sinai) and the “Southern Route” starting in middle Africa and leaving Africa via the Bab-el-Mandeb strait.

![]() 230.000 years BCE / A-PR2921

230.000 years BCE / A-PR2921

Globetrekker FTDNA places the earliest Y-ADAM DNA (A-PR2921) in the south-eastern part of Nigeria, now known as the Gashaka Gumti National Park. The “out-of-Africa” dispersals of modern humans, possibly started as early as 230,000 years ago in this region

![]() 150.000 – 60.000 years BCE / A-L1090 > A-V168 > A-V221 > BT-M42 > CT-M168 > CF-P143

150.000 – 60.000 years BCE / A-L1090 > A-V168 > A-V221 > BT-M42 > CT-M168 > CF-P143

They travelled first to the north-east corner of present day Nigeria (125.000 BCE) around Nikwa (A-V168) and then went south-east into Chad. They traversed Chad (120.000 BCE), crossed the tip of the Central African Republic and followed the northern border of the (BT-M42) Sudan (85.0000 BCE). Then into (CT-M168) Ethiopia to Djibouti and crossed the Red Sea (63.000 BCE) at the Bab-el-Mandeb strait.

Today at the Bab-el-Mandeb straits, the Red Sea is about 20 kilometers’ (12 mi) wide, but 50,000 years ago sea levels were 70 m (230 ft) lower (owing to glaciation) and the water channel was much narrower.

![]() 60.000 – 33.000 years BCE / F-M89 > GHIJK-F1329 > HIJK-PF3494 > IJK-L15 > IJ-P214 > I-L758

60.000 – 33.000 years BCE / F-M89 > GHIJK-F1329 > HIJK-PF3494 > IJK-L15 > IJ-P214 > I-L758

By following the southern coastline of Jemen into Oman they reached the north-eastern corner of Oman (F-M89) around Masqat (46.000 BCE).

They went south-west, still in Oman to Al-Jibal, then north-west through Abu Dhabi, into Saoudi Arabia (IJ-P124) and reached (46.000 BCE) the border of Iran (IJK-L15). Then westwards, passing north of Kuwait (40.000 BCE) into Iraq, north-west through Syria into Turkey to present-day Mersin.

They followed the southern and then the western coastal route of Turkey, reaching Izmir (36.000 BCE), then north to Istanbul, along the western coast of the Black Sea into Ukraine. Further to the northern border of Ukraine with Belarus and turning south-west into the Czech Republic (33.000 BCE).

EUROPE view of my (I-FGC15105) lineages through time and place and the history of my shared paternal ancestor lines.

![]() 33.000 – 20.000 years BCE / M170 > I-P215 > I-CTS2257 > I-L460

33.000 – 20.000 years BCE / M170 > I-P215 > I-CTS2257 > I-L460

Entering Austria via the north-east corner, on to (I-L758) Vienna (32.000 BCE) and travelled on through western Hungary, turning west into the Steiermark region (I-M170) of Austria (25.000 BCE).

Then south-west to northern Slovenia (24.000 BCE), westwards into the (I-P215) Swiss alps (22.000 BCE), south-east into Italy, passing Pordenone and Treviso, north into the Italian alps (21.000 BCE), then back south in the direction of the north of Venice, then east through Slovenia, crossing the southern border of Hungary.

Then they turned north to the Austrian Border and on to the west (I-L460) of south Bayern, Germany (20.000 BCE).

![]() 20.000 – 9900 years BCE / I-P214 > I-M223 > I-P222 > I-CTS616

20.000 – 9900 years BCE / I-P214 > I-M223 > I-P222 > I-CTS616

Then they travelled through Bayern in the direction of the north-west border (3150 BCE) and around present-day Regensburg they turned back again in the direction of Baden Wurttemberg (I-M223) in Germany (14.000 BCE).

Then east again to the north-western border of Austria (12.000 BCE) and on to the north border of the Steiermark region (10.500 BCE) and Burgenland, Austria (9900 BCE).

![]() 9900 -2450 years BCE / I-FGC15071 > I-BY1003 > I-L1229 > I-Z2069 > I-Z2059 > I-Z2068

9900 -2450 years BCE / I-FGC15071 > I-BY1003 > I-L1229 > I-Z2069 > I-Z2059 > I-Z2068

Then into the Czech Republic (9700 BCE) to Brno, on to Wroclaw in south-west Poland, west into Germany and reaching the eastern coast of the Netherlands around 9600 BCE. Then turning to south-east (I-FGC15071) into (9550BCE) Germany, passing Cologne, through Hessen into Bayern (8000 BCE).

Then east to the south-west border of the (Czech Republic (7000 BCE) reaching Prachatice, then west again to the south-eastern border of the Rhineland Pfalz (4000 BCE), north-west into (I-L1229) Belgium, passing Liege (2700 BCE), through Flemish Brabant, East Flanders, West Flanders, reaching the coast of the English Channel (2450 BCE).

Around that time the Wessex culture was the predominant prehistoric culture of central and southern England. The global sea level was still about 7 meters lower than today. During the Bronze Age, many people crossed the sea from mainland Europe to England.

They traveled in long wooden boats propelled by oarsmen. The boats transported people, animals and trade goods. They were loaded with metal from mines, sword precious, pots and jewellery.

Boats were very useful for transporting heavy materials such as stone. A prehistory boat found in Dover in September 1992 required 18 people to row! It dates to 1575–1520 BC, which may make it one of the oldest substantially intact boat in the world (older boat finds are small fragments, some less than a metre square) – though much older ships exist, such as the Khufu ship from 2500 BCE. The boot was made of oak planks sewn together with yew rafters. This technique has a long tradition of use in British prehistory.

My (I-FGC15105) lineage and ancient connections in present day England, Normandy France and Belgium.

![]() 2450 – 1850 years BCE / I-Z2068 > I-Y3675 > I-2054 >I-Y4746 > I-FGC15105

2450 – 1850 years BCE / I-Z2068 > I-Y3675 > I-2054 >I-Y4746 > I-FGC15105

They crossed (I-Z2068) the English Channel (2450 BCE) from Calais into south-east Kent, then north to Southend-on-Sea and west to London. From there south-west into Surrey, then south-east through West Sussex, into East Sussex, reaching the English Channel near Eastbourne. East along the coast, passing Hastings and Folkstone to Dover, crossing the English Channel again into France. Then they followed the Picardy coastline to (I-4746) Dieppe (1950 BCE) and turned east to the Cambrai area (1900 BCE).

Then back again, travelling north-east to the border of Belgium, through west Flanders, further eastward and

finally reaching the location of my own YDNA Haplogroup I-FGC15105 in Belgian Limburg around 1850 BCE.

![]()

1850 BCE – 2000 years CE / I-FGC15105 > ME

From my YDNA Haplogroup I-FGC15105 in Belgian Limburg around 1850 BCE north-west to the Netherlands and finally ending with me, Cees Kloosterman in Dordrecht, the Netherlands.

Credit:

Photo’s fom the Bab-el-Mandeb strait and the Dover boat from: Wikipedia, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

The Y-DNA chromosome is passed on from father to son, remaining mostly unaltered from generation to generation, except for small trackable changes from time to time.

By comparing these small differences in high-coverage test results, we can reconstruct a large Family Tree of Mankind where all Y chromosomes go back to a single common ancestor who lived hundreds of thousands of years ago.

- My Y-DNA Terminal SNP is I-FGC15105, subgroup of I-FGC15109, which is a subgroup of haplogroup I-M223, which in itself is a subgroup of I-M170.

- Age of I-FGC15105: ± 1900 years BCE.

Region: Sardinia and Balkans; one of the first haplogroups in Europe along with haplogroup G.

The paternal line of I-FGC15105 branched off from I-FGC15109 and the rest of humanity about 1900 BCE. The man who is the most recent common ancestor of this line is estimated to have been born around 1850 BCE.

He is the ancestor of at least 4 descendants known as I-BY18, I-BY3802, I-FT137244 and 1 unnamed line.

At the moment there are 152 DNA tested descendants, and they specified that their earliest known origins are from England, United States, Ireland, and 12 other countries.

- I-BY18‘s paternal line was formed when it branched off from the ancestor I-FGC15105 and the rest of mankind around 1850 BCE. The man who is the most recent common ancestor of this line is estimated to have been born around 800 BCE.

- I-BY3802‘s paternal line was formed when it branched off from the ancestor I-FGC15105 and the rest of mankind around 1850 BCE. The man who is the most recent common ancestor of this line is estimated to have been born around 1700 CE.

- I-FT137244‘s paternal line was formed when it branched off from the ancestor I-FGC15105 and the rest of mankind around 1850 BCE. The man who is the most recent common ancestor of this line is estimated to have been born around 1300 CE.

All human male lineages can be traced back to a single common ancestor in Africa who lived around 230,000 years ago, nicknamed Y-Adam. Here we show the SNP route from my ancestral haplogroup I-M223 (estimated to 15.000 BCE) to me I-FGC15105 and my closest connections found in ancient DNA from archaeological remains.

But the story does not end here!

As more people test, the history of this genetic lineage will be further refined.

FTDNA Globetrekker enlarged EUROPE view of my Y-DNA path to I-FGC15105

FTDNA Globe trekker EUROPE view of the lineages through time and place and to uncover the modern history of my (I-FGC15105) direct paternal surname line and the ancient history of my shared ancestors. In addition to my own (I-FGC15105) ancestral line (thick red line), the thin red lines shows lineages that went other ways and the migration paths leading up to my Ancient Connections.

Notable Y-DNA connections

- The notable Y-DNA haplogroup connections are based on direct DNA testing or deduced from testing of relatives and should be considered as fun facts.

Yes, Yes fun …, but remember DNA does not lie, DNA never lies, so they are real facts!

NOTABLE CONNECTIONS are based on direct DNA testing or deduced from testing of relatives

Ludwig van Beethoven (I-FT396000) and I (I-FGC15105) share a distant common paternal line ancestor (I-M170) who lived around 25.500 BCE.

Ludwig van Beethoven was born in Bonn to Johann van Beethoven and Maria Keverich. He was one of three children who survived infancy. At a young age, Johann promoted his son as a “child prodigy” after seeing the success of Mozart.

Beethoven had his first composition published at only 11 years old. By 22 years of age, he had composed a number of pieces, only to have them published later in his life. In his 30s, after years of public performances, his hearing loss led to a decline in concerts and a withdrawal from his social life. Despite the auditory problems, Beethoven continued to compose and perform music.

Beethoven died on March 26, 1827, at the age of 56. His last complete piece of music, Symphony No. 9, was premiered in 1824. Symphony No. 10 was left unfinished.

Previously, the cause of his death was attributed to heavy alcohol consumption. He was noted to often have episodes of fever, jaundice, and “wretched” gastrointestinal problems. But new DNA analysis shows he also may have had hepatitis B and genetic factors that played a role in his death.

Beethoven asked that scientists study his body after he died in hopes of finding the causes of his illnesses, and for the results to be made public. Now, researchers investigating his genome have made good on his request, Science News reports. They tracked down locks of the composer’s hair, which were clipped after his death and preserved by family members and collectors throughout the years, and analyzed its DNA.

From the Victorian era through the early twentieth century, giving hair to friends and loved ones was seen as a sign of sentimentality. Although it was originally used as a sign of mourning, giving a loved one your hair was later used as a memento to give to them.

The University of Cambridge, with help from FamilyTreeDNA and others, examined the hair in an effort to understand more about Beethoven. Members of the FamilyTreeDNA Research and Development team were able to assist with confirming the validity of Beethoven’s hair.

Ludwig van Beethoven and I (I-FGC15105) share a distant common paternal line ancestor who lived around 25.500 BCE.

Testing Beethoven’s hair